During the early 20th century, many of these artists acknowledged the influence of Pablo Picasso and cubism—and if they didn’t, odds are they were lying. Artists also characteristically connected their work to a religion or philosophy that promoted simplification, though this connection has probably been made less and less significant due to the dominance of formalist readings of art history.

One of the most well-known abstract artists of the 20th century is Piet Mondrian, and his path to abstraction had all of the aforementioned attributes. However, while his abstract, gridded paintings grace the walls of museums around the world and have become icons of modern art in a way few others have, it’s unclear to most people how he arrived at his well-known style.

Born in Holland in 1872, Mondrian’s initial mature works focused on nature and looked to fauvism and luminism for inspiration. Mondrian soon came under the influence of Vincent van Gogh. If one looks at Mondrian’s works between 1908 and 1909, particularly his Red Tree(1908), it’s easy to pick out characteristics we commonly ascribe to Van Gogh, such as the repetitive (almost vibrating) brushwork, the placement of the tree within the composition, the use of bright colors, and the melding of the tree into the landscape.

1911 was a pivotal year for Mondrian, arguably the most important of his career. It was then that he came across the “Moderne Kunstkring” exhibition at the Stedelijk Museum, which included the works of Paul Cézanne, Picasso, and Georges Braque and brought cubism to Holland. This show dramatically changed his idea of what kind of painter he wanted to be. It also made him change his mind aboutwhere he wanted to be: he moved from Holland to Paris before the end of the year.

In Paris, Mondrian’s work quickly took on cubist attributes. Initially, his paintings echoed the so-called analytic style of cubism, particularly its palette of beiges, grays, and ochres as well as its use of straight lines and arcs to articulate objects and space. And while Picasso and Braque characteristically created portraits or still-lifes, Mondrian’s subject matter was nature, realized through a systematic network of right angles and grids. Additionally, his use of space was much flatter and less ambiguous than that of cubism’s obscure three (or four) dimensions.

What motivated Mondrian towards abstract art was something much more mystical than that of Picasso and Braque; in his words, he aimed “to articulate a mystic conception of cosmic harmony that lay behind the surfaces of reality.” His thinking was based on his belief in Theosophy, a philosophy that gained a following in the United States in the late 1800s. One way his beliefs manifested themselves in his works was through horizontal and vertical axes, which in his works from around 1913, looked like crosses. Such crosses reflected Mondrian’s belief that the universe played host to a constant conflict between opposing forces, whether they were dichotomies of good and evil, positive and negative, masculine and feminine, or dynamic and static.

In 1914, Mondrian went to visit his sick father in Holland and then, due to the outbreak of World War I, couldn’t go back to Paris. He wouldn’t return until 1919. But in Holland, Mondrian methodically endeavored to distill his painting style, and it was during this time that the aforementioned horizontal and vertical axes emerged as the major organizing principles of his increasingly abstract images.

As of 1916, Mondrian began doing away with subject matter entirely in favor of what he increasingly felt was the irreducible structure of the world: a grid of perfectly parallel and perpendicular lines, comprised of his crosses, now connected. At first these grids extended in a uniform way across the canvas and were combined with colors, such as pink, blue, and orange.

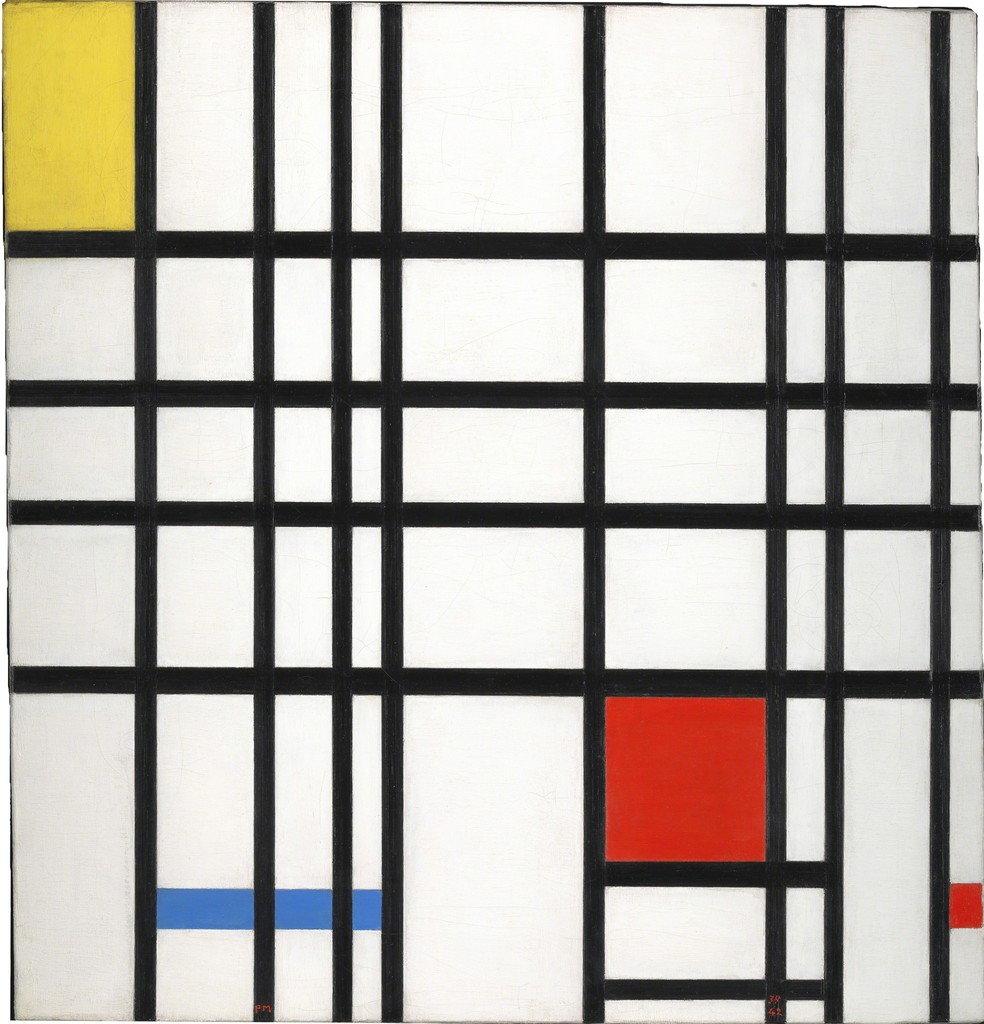

Eventually Mondrian’s grids included larger squares and rectangles of different sizes and his palette was reduced to primary colors. The beginning of this approach can be traced back to 1920, and it’s at that point that Mondrian began making the works that have become synonymous with his name.

It was also during this time that Mondrian began writing about his work. In one of his most important essays, “Neo-Plasticism in Pictorial Art” (1917–18), he explained his approach to abstraction. Among other things, he cited the mechanical automatization of life as the impetus that led so many artists to abstraction—which he argued was internally motivated, as he considered abstract art to be a representation of the human mind. Mondrian also proposed that beauty is based on a relationship between complementarities: balanced and equivalent forces that he believed were the purest representation of universality, of the harmony and unity that are inherent characteristics of the mind and of life, and of anything. Pictorially for Mondrian, this took the form of the two lines that create a right angle, which he thought expressed, in a perfect harmony, the relationship between two extremes. Moreover, Mondrian believed that the use of complementary colors and sizes reinforced this balance.

The story of Mondrian’s emergence into an abstract artist is just one of many narratives that are so integral to 20th-century art history. They’re often extremely satisfying narratives to share and listen to because of the logic of their artistic progression and one wonders if we’ll ever get to a point again where the crux of an artist’s biography documents such a progression. At the same time, modern and contemporary art offers an endless array of stories of process or an artist’s “maturation.” These complex, non-hierarchical, and postmodern narratives offer many new ways of thinking about the act of making and are, realistically, the only accurate stories for the art of the present day.