Carrie Moyer, “Intergalactic Emoji Factory” (2015), acrylic and glitter on canvas, 72 x 96 inches (all images courtesy of DC Moore Gallery, New York)

When Carrie Moyer and I decided to have a conversation, her recent paintings were already at DC Moore Gallery, where her solo exhibition —

now on view — was soon to open. We met there after hours, and over beer and chips, and talked among the works leaning against the walls. There was an odd and disorienting friction to our informal hangout, suddenly set against the backdrop of the well-lit gallery, but Moyer seemed perfectly at ease.

Moyer’s work, too, deals with intervention, but its achievement is that fluidity replaces jarring juxtaposition. In this, it reflects her years of experience as an activist who designed public and street art campaigns with

Queer Nation and

Dyke Action Machine!. In her paintings, flat planar “cut” shapes are interwoven with translucent passages. Craft materials like glitter are contained within gestures we normally associate with heroic abstraction.

Carrie Moyer (courtesy the artist) (click to enlarge)

The paintings often have symmetrical, overall forms, which are suggestive more than graphic. They are elegant and beautifully constructed, even though they play with the noise and glare of popular visual culture. They seduce us, inviting us to pull them apart, but their construction feels illogical, difficult to tease out of their overall gestalt.

Moyer was born in Detroit, Michigan in 1960. She received a BFA from Pratt Institute in 1985 and an MFA from Bard College in 2000. She is currently a Professor at Hunter College. With photographer Sue Schaffner, she co-founded the public art project Dyke Action Machine!, active in New York City between 1991–2008. She has also written extensively about art for

Art in America,

The Brooklyn Rail, and

Artforum, among other publications and exhibition catalogs. She was the subject of a solo exhibition at the

Worcester Art Museum in 2012, and a traveling exhibition,

Carrie Moyer: Pirate Jenny, which originated at the Tang Museum of Skidmore College, Saratoga Springs, New York, in 2013. She had several exhibitions at Canada Gallery between 2003 and 2011. She is now represented by

DC Moore Gallery, New York, where a solo exhibition is on view through March 26, 2016.

* * *

Jennifer Samet: You have said that your parents nurtured an interest in art. Where did you grow up? Were there specific experiences you had with art, or specific works of art, which you consider formative?

Carrie Moyer: I was born in Detroit, where my family has longstanding roots. My grandfather was a policeman during the Detroit riots in the 1960s. But I had countercultural parents who put us in a van when I was nine and drove us out to California with all of our belongings. My family lived all over the Northwest for the next 10 years — California, Oregon, and Washington.

Carrie Moyer, “Cloud Comb for Georgia” (2015), acrylic and flashe on canvas, 72 x 60 inches

My mother was really interested in art and encouraged my sister and me to become artists. She often took us to the Detroit Institute of Art before we left for the Northwest. Diego Rivera’s gigantic fresco cycle, “Detroit Industries” (1932–33), made a big impression on me. I was exposed to a lot of pictures through books as well. A favorite was a book on the Blaue Reiter that included Alexej Jawlensky’s painting, “Portrait of the Dancer Aleksandr Sakharov” (1909), which I thought of as “my painting.” It is intensely colored, filled with feeling, and the dancer looks very demonic and androgynous.

I wasn’t interested only in visual art; I was also involved in various kinds of dance throughout my childhood. I ended up getting a full scholarship to Bennington College to study modern dance. Because I lived in remote places, I was a bit of an autodidact and had done a lot of research on Martha Graham and the history of modern dance. She taught at Bennington; that was where all her ideas came to fruition.

I had to quit after a year because I was in a serious car accident, and wasn’t able to dance for a while. So making pictures and visual art turned out to be what I did. I studied at Pratt. When I finished school I had that horrible year that most art students have after they graduate, where they wonder, “Can I really do this? Do I want to do this? Nobody is telling me to make a painting anymore.” I’d had a couple of teachers at Pratt who noticed my budding feminism and helped me get an internship at Heresies: A Feminist Publication on Art and Politics. It was the first time I was around artists who were also activists, and it was exciting.

JS: Yes, you became involved with agitprop work and co-founded Dyke Action Machine! Can you tell me about that work?

CM: The late 1980s and early 1990s were when the AIDS crisis was coming into public consciousness, and it sparked queer activism. Suddenly what was happening out in the world and on the street felt more urgent than what could happen in the privacy of the studio. I come from a lower-middle-class family and, after Pratt, I struggled with questions like “What is art going to do in the world? How is it going to help someone or change something?” Painting felt irrelevant to me in that moment; I considered whether it was an elitist occupation.

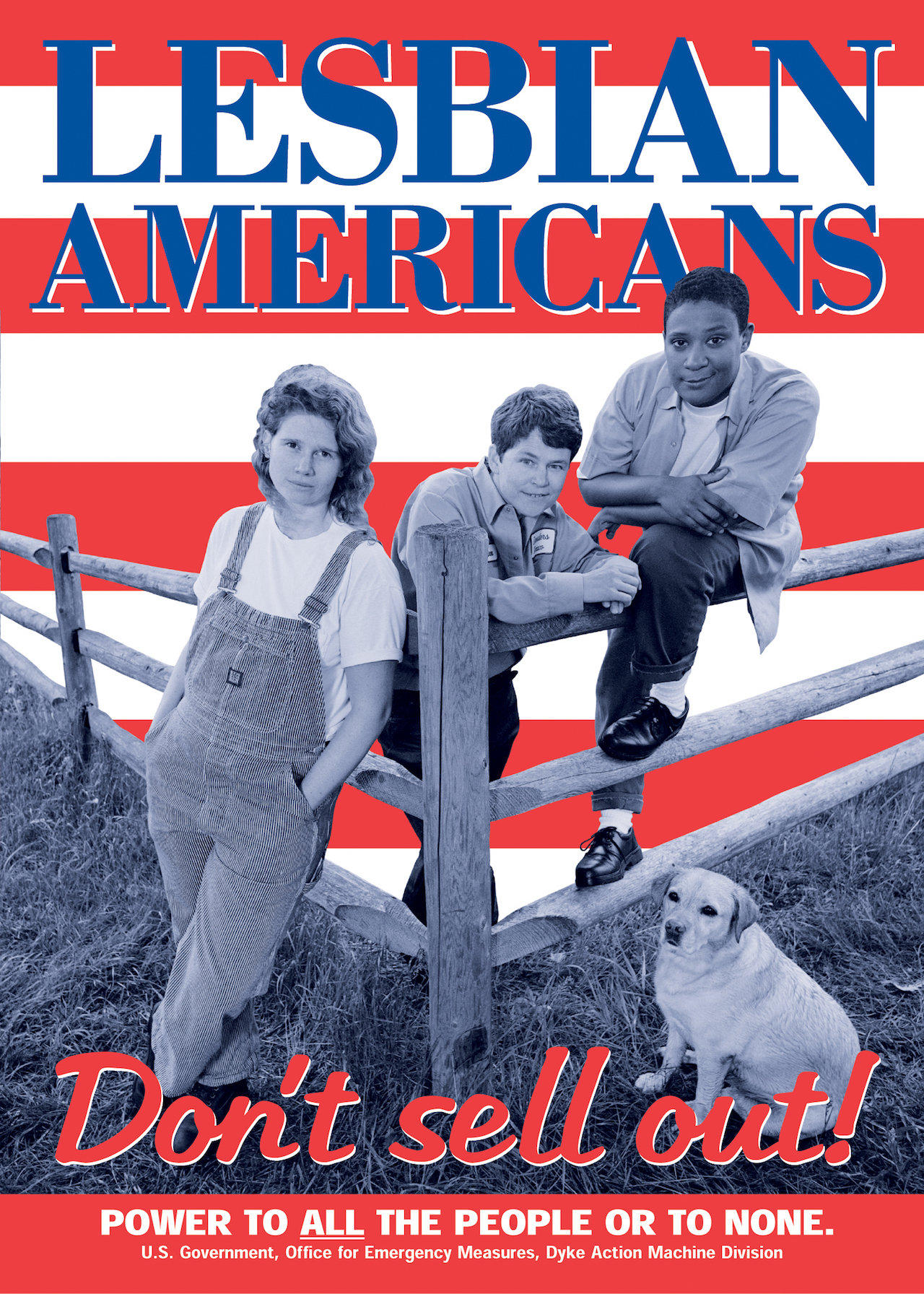

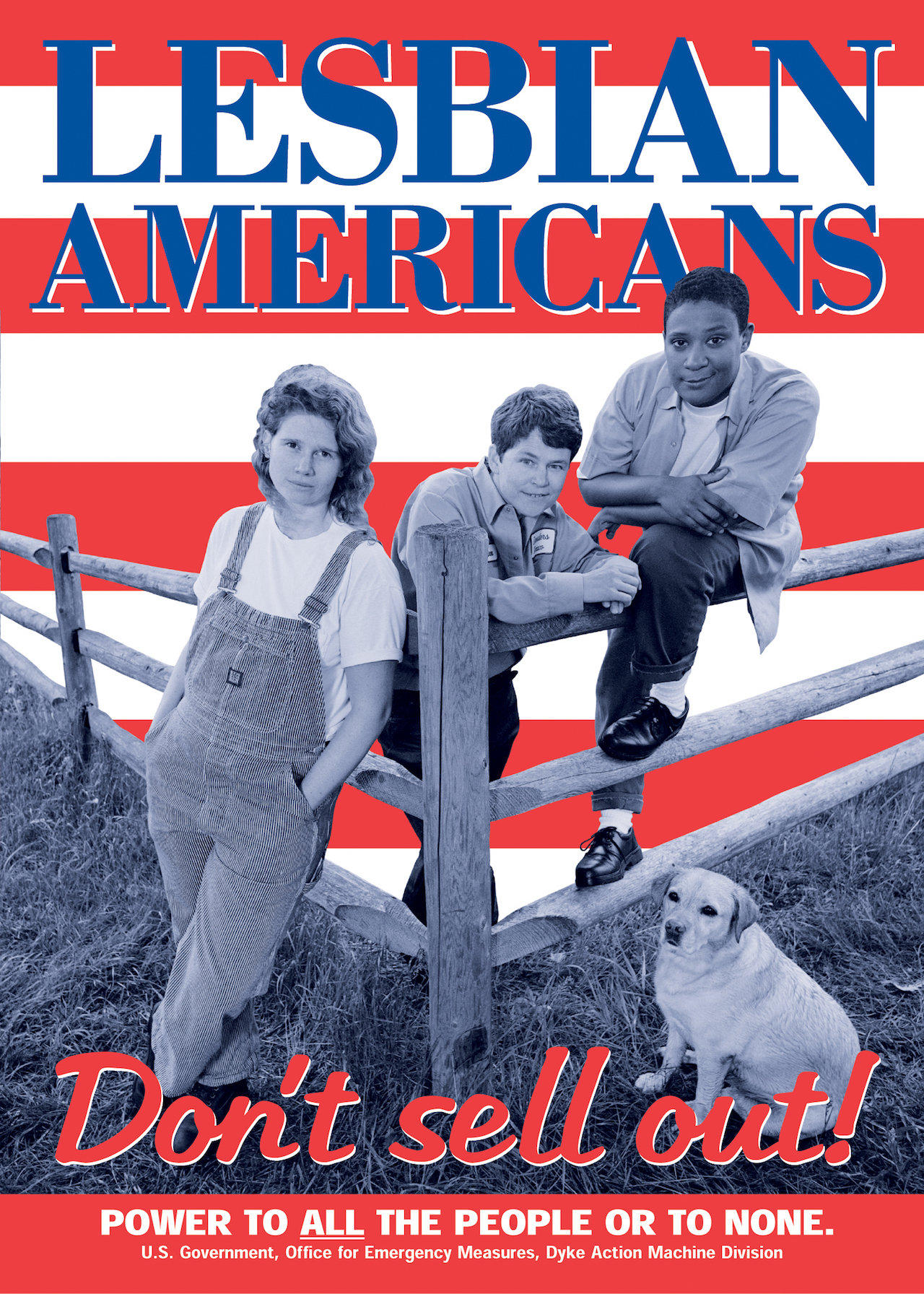

Dyke Action Machine!, “Lesbian Americans: Don’t Sell Out” (1998), 4/C offset poster, 24 x 36 inches, 5,000-piece campaign wheat pasted in New York City, June 1998

I began working in advertising agencies as a graphic designer and gave up my studio. All my “art” energy got channeled into queer civil-rights activism. Dyke Action Machine!, the public art collaboration I started with photographer Sue Schaffner in 1991, was an offshoot of Queer Nation. We were interested in the work of Jenny Holzer, Barbara Kruger, and other forms of conceptual art that played with language and public address.

Many of our activist friends worked in the advertising business and used their skills to make graphics about the AIDS epidemic. Gran Fury, and the group that came up with the “SILENCE = DEATH” logo were huge inspirations. Sue and I wanted make posters that took on the double invisibility lesbians faced in both the straight and gay worlds. At the time, queer activism also focused on making gay people more visible to the public at large — “outing” celebrities was a tactic for a while. Dyke Action Machine! did its part by creating poster campaigns that were wheat-pasted throughout the city from 1991 to 2004.

JS: Eventually you got back to painting. Did your graphic work affect your painting?

CM: Yes, when I returned to painting I was thinking as an agitprop maker. The romance of painting still felt very suspect. I was thinking about the history of 20th-century political graphics, from Constructivism to Atelier Populaire, the group that created the posters during the May 1968 protests in Paris. I wanted to set up a dialogue between historically loaded images of Lenin or Mao and painterly gestures. In retrospect, the paintings presented a struggle between intuition and a set of signs. It was a way of backing into painting and feeling like it had validity or agency.

That didactic approach — hard-edged, opaque shapes coexisting with instances of pouring — was part of my work for a long time. It was almost like a cliché about how the two sides of your brain work: left side/right side, or mind/body. It set up a false dichotomy that has morphed over the years. Now I think of them all as gestures that act on each other, rather than an either/or.

arrie Moyer, “Cloud 9” (2016), acrylic and flashe on canvas, 72 x 60 inches (click to enlarge)

JS: Your discussion of the graphic shapes reminds me that you use collages as a preparatory stage in your process. How and why did you start using collage this way?

CM: In the early 2000s I started using small collages as a starting point for the paintings. At one point the collages were only black-and-white, and then I started to use Color-Aid paper. I sit around and basically draw with a blade, building up a pile shapes that I put together. I use collage to figure out spatial relationships and composition. The color just operates as a way of separating things.

JS: You have spoken about acrylic paint being a more “lowbrow” medium. What do you mean by this?

CM: When I went to art school, we were taught using oil paint; that was “real” painting. No one used acrylic. So when I returned to painting, I wanted to use a material that didn’t have a lot of baggage attached to it. I wasn’t thinking about Helen Frankenthaler or anything. I was just thinking — this is not going to be reminding me of history every time I make a mark. Also, it has a universe of associations outside of itself.

In the book Chromophobia (1997), David Batchelor discusses how oil paint is made to do one thing only and that is to make oil paintings. On the other hand, acrylic or plastic is part of everything. It’s part of furniture, phones, make-up, everything — it’s a really different thing. It’s populist and commercial. It’s plastic paint, and it can be dazzling!

I was thinking about how the issue of taste operates in modernist art. Younger artists might look at Judy Chicago’s “The Dinner Party” (1974–79) and think, “That is so cool.” But people from my generation get a stomachache when they go into that room at the Brooklyn Museum. For feminist artists of my generation, it’s even more complicated and challenging. The project was way ahead of its time in many ways — it pulls craft into the mix and counters every idea about taste attached to High Modernism.

Carrie Moyer, “Meat Cloud” (2001), acrylic, glitter on linen, 72 x 84 inches

In my work, there’s a playful relationship to some of the most traditional and clichéd imagery of painting, such as landscape, flowers and female figures. It sneaks in there in humorous ways. When it shows up in the work, I embrace it: yeah, those are boobs in there.

I’m also interested in breaking conditions that are supposed to go with certain kinds of painting. For example, a flat, Greenbergian abstraction would never include shadows. Tacky! The space in a Hans Hofmann painting is made through color. I like to have illusionistic space and flatness in the same painting. Somehow this goes back to working as a designer in the advent of the desktop computer. In the old days, before people designed everything on a Mac, nothing had a “drop shadow.” The drop shadow is an invention of Microsoft. It is a sign for fake space.

JS: You’ve told a story about a teacher at Pratt saying that you paint holes because you are a woman. Is embracing cliché a way of reacting against those kinds of statements?

CM: People still use this terminology, this idea of what a man would paint or what a woman would paint. They say something looks feminine or masculine. Those are platitudes that exist around content or process, and it’s something I’ve played with for a long time.

I studied feminist art from the 1970s, but there weren’t many painters to look to. Painting was part of feminist discourse by virtue of its absence. It was too embedded in the patriarchal history of Western art. So how could you touch on that in painting? How does feminist content show up? Would you be coyly suggestive like Georgia O’Keeffe was?

Stieglitz turned O’Keeffe’s work into cliché about femininity as she was making it. Who knows what Georgia O’Keeffe was thinking when she made those paintings. But they are crazy sexy paintings. She used very restrained, neat little academic strokes to build up a picture. There is a funny friction between the repressed way that it is painted, and the voluptuous image created through extreme cropping.

Carrie Moyer, “Vieni Qui Bella” (2016), acrylic and flashe on canvas, 72 x 84 inches

JS: How do you think your painting relates to your activist work?

CM: I don’t claim these paintings as activist work. What is political about my painting, if we can even say that, is that it is experiential. They are abstractions based on my own history, even though they address the history of 20th-century painting, or at least certain parts of it.

I’m also positing ideas about pleasure — both pleasure for me, and pleasure for the viewer. This feels decadent right now, because it is not about the work being a commodity, it’s about the pleasurable experience of looking. Hopefully the paintings operate at degrees, meaning people who aren’t involved with the history of painting can get something out of it. I’m not interested in intellectual opacity or “enlightening” the viewer. I’m going for beauty, seduction, and play — a physical experience, an optical experience.

However, my first audience, the one I’m thinking about in the studio, is always other painters and people involved in the history of painting. What dialogue am I in with painters from the past? I think about painting in terms of the politics of who is making it, and when it gets made. For instance, isn’t it interesting that we are living in this moment when there are a lot of prominent women abstract painters? This is very unusual.

JS: Do you have any theories about why that is?

CM: For me, it’s about considering the very familiar language of Abstract Expressionism and Minimalism and whether it constitutes a “male gesture.” It is about how we work around that, and reinvent it, and own it. There are all sorts of interesting inventions because of it.

Carrie Moyer, “Candy Cap” (2016), acrylic, glitter, and Flashe on canvas, 72 x 96 inches

I recently wrote an essay on Louise Fishman, who is the subject of a big retrospective at the Neuberger Museum of Art this spring. When she began painting in the 1950s, she was really into Franz Kline and the big, gestural Expressionist paintings that became signifiers for the male artist. For young artists, finding your “people,” intellectual role models, mentors, is about self-definition. It’s political, how you see yourself in the world. When I was in art school, mine was Elizabeth Murray.

JS: You mentioned being a dancer. Do you think dance is related in any way to your work or process?

CM: Dance is totally related to process. It is a part of what happens in the studio. The process becomes a kind of choreographed set of actions that are chemical and physical. You start to evaluate what might happen by using a certain amount of water, by pouring at a certain height or angle.

The physicality — an idea about a joy based in the body — is what interests me. Pouring is time-based, being aware of when the surface is going to dry or close down. You could paint for a few weeks, or a few days, to set everything up for that moment. That is how these paintings go. The longer I keep working in this manner, the more I realize it is about anticipation, about creating the conditions for something to happen.

Carrie Moyer, “The Green Lantern” (2015), acrylic and glitter on canvas, 72 x 60 inches (click to enlarge)

A paradox of getting older is that I am less interested in explaining the meaning of work. When I was younger, I always used to hate it when one of my teachers, or an older artist would say, “I don’t have anything to say about that painting.” It always felt like a copout. But now the culture of the art world has swung in the other direction, in which every aspect of art needs a rationale.

Museums are striving to be hubs for the community, and with that, trying to ensure people are not intimidated by art. A solution is to offer three-paragraph wall labels about every piece. Art is being proffered as a commodity that is fun and social, but it’s no longer something that is left just to work on the viewer. And that is the most important part of what we do.

The amazing thing that happens in the studio is that you give yourself permission to invent something. You can work with something you can’t necessarily explain, and can use that space of un-knowing as a generative place. How do you make something you haven’t seen before? This takes a very long time. It feels so precarious, but also really amazing.

Right now I have more trust in the gut than the intellect. Something that people don’t often talk about is how much fun we’re having in our studios. People might wonder, “Why are you spending all your time alone, doing this?” Well, it’s because it’s really fun! Mostly, our culture treats leisure or work like this toggle switch: I am at my job or not at my job. Being in the studio is a whole other kind of engagement. There aren’t any parameters unless you create them. Your job is to batten down all your judgment so you are free to do something.