Disconnect the Dots

Cynthia Thatcher explores the teachings on happiness that the Buddha gave to Bahiya.

By Cynthia Thatcher

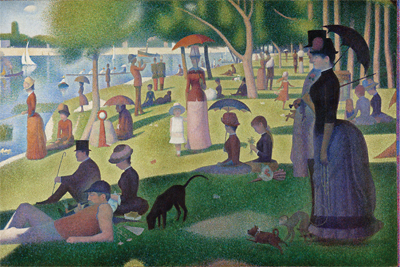

The painting was George Seurat’s Neo-impressionist work A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte, his famous scene of Parisians in a waterside park. As my eye scanned the canvas, jumping from boats to people to clouds, it caught on a tree.

Here were no seamless bands of color, no blended patches of tint as in so many other paintings. The tree was made up of countless specks—a smattering of separate orange, yellow, and blue dots. The boats on the water, the people on the lawn, their faces and clothes—all were a sprinkling of motes, as if the canvas had been caught out in a rain of paint.

Out of the blue, I remembered the ascetic Bahiya, who asked the Buddha to teach him the path leading to happiness. “When seeing,” the Buddha said, “just see; when hearing, just hear; when knowing, just know; and when thinking, just think.” (Udana 1.10) It was all in how you looked at it. The Bahiya text is deceptively simple. In one sense, it means: Don’t daydream. Pay full attention to what you’re seeing. But there’s more to these words than you might think. Or maybe less.

I did a double take when my meditation teacher, Achan Sobin Namto, explained the deeper meaning of this attention practice. “If we could focus precisely on the present moment…,” he once wrote, “the eye would not be able to identify objects coming into the area of perception.” Ultimately, he said, following the Bahiya formula meant to see mere color instead of recognizing what you were looking at. It was possible to do this because there was a split-second time lag between (1) sensing the bare image and (2) recognition. (The same applies to perceiving sound, smell, taste, touch, and mental phenomena such as feeling.) If mindfulness were quick enough, you could catch the moment of bare seeing.

Wait a minute—had I heard right? “So if I really stay in the present moment,” I asked, “I’ll see a cup in front of me and not recognize it?”

“Absolutely,” Achan said.

“When pigs fly,” you might be thinking. Achan Sobin was once skeptical, too. “Impossible!” he’d said when his own instructor explained the idea. Later he spent decades teaching it to others.

To understand the teaching Bahiya received, it helps to remember the Buddhist distinction between ultimate and conventional truth. Consider the painting again: close-up, you see meaningless flecks of tint that don’t represent anything. Beings and objects, time and place, have vanished. The Seine, the trees, the woman’s face—all have exploded into particles, scattered across space. But when you step back from the picture, recognizable shapes leap into view as the eye “pulls” the specks together.

The individual points of color, and the identities that coalesce when the eye connects them, occupy the same space. From one vantage point there is a vista of permanent beings and things. From another, there’s no solid ground—only empty sensation that you can’t name. The painting presents a visual metaphor for conventional truth versus ultimate reality; self versus nonself.

The Bahiya teaching tells us to break our habit of looking at experience in terms of labels or concepts and instead observe ultimate reality directly. This is done by paying attention to bare seeing, hearing, smelling, touching, tasting, and feeling in their most primitive state, before your inner narrator names them. By repeatedly watching these events you’ll discover there is nothing personal about the act of perception.

Normally you think, “I am seeing.” Yet in the ultimate sense, the seeing that happens isn’t anyone’s. Although hearing occurs, there’s no self who hears. Rather than a homogeneous entity, we find a collection of parts. Unless observed closely, what we regard as the self appears to be a solid, personal identity that perceives things. But in truth there is no metabeing who unifies the parts. All our actions happen without an agent, or self, performing them. There is no seer, just the seeing; no hearer, just the hearing.

Distinguishing the tree in the painting from the specks it consists of may be a walk in the park. But it’s much more challenging to learn to separate the named things we’re familiar with from the bare seeing, hearing, and touching of actual experience. To master this skill, we must turn our attention again and again to direct experience until our mindfulness is fast enough to notice bare sights, sounds, touches and so on before recognition takes place. Even when practicing very diligently, the remarkable experience of observing bare sense-perception usually only happens when we’re least expecting it.

One morning, during a meditation retreat, I heard the sound of a bird. A mundane event, right? Except the sound was a quick whiplash of sensation that wasn’t connected to any named thing—least of all a creature called “blackcapped chickadee.”

At first I didn’t even recognize the sensation as an auditory form as opposed to a sight or smell. The next moment, the mental dots connected and the word “bird” slid into the mind. But the label didn’t erase the experience. Some veil had slipped, if just for a second.

When Achan Sobin walked in, I could hardly wait to blurt out: “It’s just a sound! It has nothing to do with the bird.” The event had somehow shaken my world.

“Nothing to do with the bird?” he asked.

Bingo.

He laughed and nodded. “Very good!”

“But it’s not even a sound.”

“No,” he confirmed, “by the truth, not even a sound.”

Stories of meditators experiencing bare awareness are common in the Buddhist world. The English monk Kapilavaddho Bhikkhu describes casually looking at his left hand, when “suddenly… the hand had lost all sense of solidity… Here, all that was presented to the eye was color.” In her memoir Hidden Spring: A Buddhist Woman Confronts Cancer, Sandy Boucher reports that when she first tried to mindfully observe pain, the feeling seemed very solid and she wanted to scream. But when she stopped labeling the pain as anything and ceased defining it as part of her self, a shift happened: “Finally there were only the sensations—without a name or a definition or association—only an elemental vibration of phenomena expressing life. For a few moments I was able to stay with this… separate from my identifications and desires. Then I fell back into my ‘I’ and experienced the sensations as if they were attached to ‘me,’ and they became pain again.”

The clincher for me came when my Christian mother attended a meditation retreat, expecting nothing but sore knees. “For the first time,” she said afterward, “I’d seen color only, without any label attached, and only a moment later did I realize I’d been looking at the familiar orange drapes.” But is it possible to function in ordinary life when seeing only color patches? No, you have to recognize sights and other sense-impressions when writing, cooking, and even teaching the dharma. To follow the Bahiya teaching doesn’t mean giving up the concepts of conventional reality altogether. The point is to devote some time every day to formal insight meditation during which you focus on bare sense-perception, until that practice gives rise to clear and direct insight into nonself (during daily actvities you can use broader attention). By paying attention to sensory experience as it is happening—and not getting caught up in the labels, preferences, thoughts, and emotions that happen in the split seconds after bare sense-data impinge on our awareness—we learn to see the suffering involved in getting caught up. And by seeing that suffering, we learn to free ourselves from it.

We learn this because when we can separate bare perception from conventional meanings, the feeling that an experience is happening to “me” begins to drop away. We discover that instead of being inherent in perception, the notion of a self is a deep-seated belief unconsciously added to it. If we focus on stopping short at bare perception before any concepts arise to complicate it, nonself will get clearer and clearer, since it’s the natural state of things, always there to be seen. And the clearer our understanding of nonself, the less we’ll suffer. Although initially the clinging to self disappears only when we’re very mindful, those moments free of delusion give deeper insight a chance to arise, and eventually wisdom becomes strong enough to trigger a permanent change of outlook. But even before that permanent change, the memory of having seen nonself directly—even for one moment—stays with us, and most of the time we feel much lighter than we used to.

For most of us, however, the permanent change of outlook is a long way down the path. Even observing bare sense-data for a few moments, if we truly do it, is nothing to sneeze at. The Burmese meditation master Mahasi Sayadaw wrote, “It is no easy matter to stop short at just seeing.” Although the aim from day one in insight meditation practice is to observe bare perception, it won’t actually happen, he says, until mindfulness and other factors reach an intermediate level.

In the early stages of meditation, you’ll still perceive only named, conventional objects, which are concepts. That’s fine. But it will help to focus on the knowing itself––that is, on the act of hearing, touching, seeing, and so on––rather than on the sense-impression per se. Further, right understanding will guide your effort toward the target. If you realize the aim is to know bare perception before the mind names or describes the experience, you’ll eventually be able to do it—paradoxically, though, only when you aren’t consciously trying to. (And by the way, although I’ve been emphasizing color and sound, in practice you’ll observe tactile sensations more often than any others.)

As we reach the intermediate stages of insight meditation, we begin to see that our experience isn’t an unbroken flow but rather a series of separate moments of consciousness that arise and die out, one at a time, with incredible speed. The mind that sees something quickly dies, and a different consciousness hears a sound. No self or soul carries over from one perceptual act to the next. In truth, your life-span is only one moment long. Buddhaghosa, the fifth-century Indian Buddhist scholar, wrote: “The being of the present moment has not lived, it does live just now, but it will not live in the future.” While you’ve been reading this article, thousands of different “beings” have arisen and died in the very chair you’re sitting in. No wonder the Buddha called consciousness a “conjuring trick”! (Samyutta Nikaya 22.95)

In daily life the separate moments seem to blur together, concealing the truth that birth and death are always occurring. This is part of the reason we buy into the conventional picture of a lasting self. Nonself only begins to be clear when the illusion of seamlessness disappears and we experience the gaps in the continuity, when we actually see the mind and its object arising and dying together from instant to instant. Then we may discover, as Mahasi Sayadaw wrote, that “the concept of a human form with its head, hands, and other parts is nowhere to be found.”

We’re not going to live in a world of nameless sensation forever. But glimpsing nonself clearly, even for one moment, puts ordinary truth in perspective. When the conventional picture returns, we regard it differently. What a relief when we no longer have to take our “selves” so seriously! We can still be responsible family members and effective employees; but we won’t suffer as much when problems arise. The anger, hurt, or fear that usually comes up when the boss berates us—or a loved one betrays us or the body gets sick—will be much weaker and shorter-lived. And when it’s absolutely clear that no phenomenon, including consciousness, truly belongs to us, we can realize the happiness of nibbana as Bahiya did.

No comments:

Post a Comment