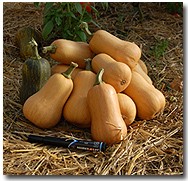

A few years ago, Mazourek, a vegetable breeder and professor of plant science at Cornell University, went to the Blue Hill restaurant in New York to sample the dishes that Barber, the chef, had made from the some of Mazurek's' newly bred organic vegetables. He was expecting a good meal, he recalls—after all, he could vouch for the quality of the raw ingredients—but he was blown away by the flavor that Barber and his colleagues had coaxed from the vegetables, particularly a tiny, tan variety of butternut squash called “Honey nut.”

Mazourek, who had never thought much about how his foods would be cooked once they left the farm, asked Barber what he had done to prepare the Honeynut. After the chef explained his technique, he asked a question of his own: The Honeynut didn’t store as well as other types of winter squash, Barber said, which meant the restaurant couldn’t keep them on the menu very long. Was it possible to develop a squash with all of the flavor, but a longer shelf life? There in the kitchen, Mazourek launched into an explanation of his classical breeding techniques, a conversation that quickly became a back-and-forth about what chefs needed and what plant scientists could provide.

Organic Seeds)

Mazourek is one of only a handful university-based researchers in the United States who develops new organic fruits or vegetables. Most of his colleagues, he says, focus primarily on traits like storability and shipability, with flavor further down on the list of priorities.

The first step in classical plant breeding, Selman explains, is identifying two different plants in the same species with the desired genotypes. “Maybe one has really great disease-resistance and one has fantastic flavor,” she says. Breeders will get the two plants to exchange pollen, save the seeds, and grow them again, picking the most desirable plants from this second generation and planting their seeds. They do this over and over until the traits have stabilized—that is, they always show up when those seeds are planted.

The diversity that can be achieved through classical plant breeding is as impressive as anything food scientists can dream up in a laboratory. For example, Jim Myers, a professor of vegetable breeding and genetics at Oregon State University, created the Indigo, a purple-shouldered variety of tomato with higher levels of antioxidants. Both he and Cornell’s Mazourek have developed habañero peppers that have all the flavor of the original, but none of the heat.

Why would anyone develop new edibles that are barely edible? The short answer is that priorities in the food system changed after World War II: Grocery stores and large-scale industrial farms wanted foods that looked uniform, could be shipped long distances, and stayed fresh in storage. They wanted plants that produced a high volume of food and could be harvested by machine.

Today, consumer tastes are forcing a change, as more people value food that’s organic or locally sourced—but the system for supplying fruits and vegetables that meet this changing demand has been slow to catch up.

That’s where people like Selman come in. Her work on “culinary breeding” started in 2011, when she organized a tasting event for Frank Morton, an independent plant breeder and the owner of the seed-supply company Wild Garden Seed. Morton had developed several new varieties of red roasting peppers for a farmer, but he had no way of determining which was one was the best of the crop.

Selman arranged for a panel of Portland chefs to try nine peppers, including four of Morton’s. There was a clear winner: a long, smooth pepper called the “Stocky Red Roaster.” Wild Garden Seed carried that variety the following year. Then something happened that Morton didn’t expect: Portland chefs started asking for the “Stocky Red Roaster” by name, and farmers, in turn, began clamoring for the seeds. Morton sold nearly his entire stock.

These showcases expose breeders to the innovative ways chefs can cook with their foods. One hit from this year’s showcase, for example, was an apple-parsley granita served over buttermilk mousse, made by the chef Nora Antene from the restaurant Le Pigeon. Last year, the same chef had made a popular habañero-orange sherbet.

“It totally blew my mind,” says Myers. “That’s something I would have never thought you could do with these items.”

With the Culinary Breeding Network, he continues, “there’s this cross-fertilization with breeders and chefs. I take that information back to the field and think about what I need to do in terms of breeding. And I think the chefs are excited to get these novel things to work with.”

Joshua McFadden, the executive chef and a partner at the Portland restaurant Ava Gene’s, is one of them. A former farmer and an alumnus of Blue Hill, he’s currently working with Ayers Creek Farm to help them refine their winter melons—he and his staff save the seeds from the tastiest fruits they use and send them back to Ayers Creek for planting.

“I want flavorful food,” McFadden says. “There’s nothing more important than flavor. If you’re breeding for flavor, a lot of the crops that were lost due to scalability and industrialization will come back.”

No comments:

Post a Comment