China’s Coming Great Depression

China is steering down the same course that took the United States into its Great Depression.

China is on the road to its own Great Depression. The causes of our Great Depression are still hotly debated, but the best explanation comes from Friedrich Hayek, aided by the work of Milton Friedman: the depression was brought and prolonged by loose monetary policy in the 1920s, followed by a too-tight money policy after the initial bust. The misguided supply-side policies of Hoover and Roosevelt served to postpone the recovery further. China’s depression will stem from similar causes.

China’s massive over-indebtedness, which underlies its current slowdown, is the inevitable outcome of its easy money policy of the recent past. But China’s monetary policy is increasingly becoming far too tight, even as China’s central bank attempts to accomplish the opposite. Misguided supply-side policies will compound these problems in a lurch away from economic liberalization, toward increased state control of industry. Put all these factors together, and China heads into a depression.

To better understand, start with how China got into this mess.

Inflating the Money Supply

Beginning in the mid-1990s, China’s central bank, the People’s Bank of China (PBOC), pegged the yuan—also known as the renminbi (RMB)—to the dollar (USD) at a price lower than the RMB’s true market value. A cheap RMB made Chinese products cheaper for Americans to buy, which boosted Chinese exporters. In practice, the peg meant that when exporters were paid in dollars, the PBOC would buy the dollars for RMB, but would pay more RMB to the exporters than the dollars were worth. For example, the RMB that an exporter would receive from the PBOC in exchange for $100 it earned abroad would, without the peg and the capital controls the peg requires, have enabled the exporter to buy over $100 worth of goods overseas.

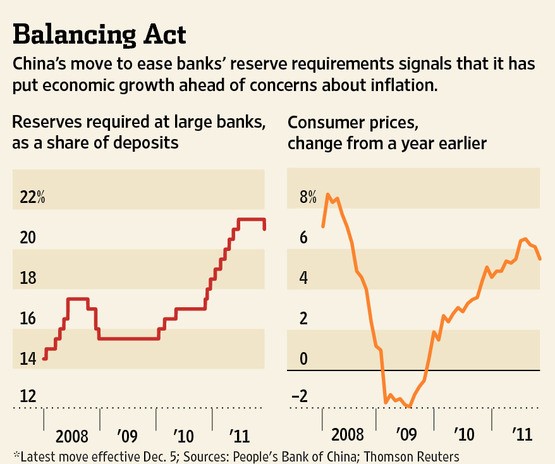

There were two side effects of China’s currency peg. First, when Chinese exporters were paid more RMB than they would received in the market, this amounted to the PBOC printing extra RMB and injecting it into the economy. Some of the new money was sterilized—reduced in its power to push up prices—by lifting banks’ reserve requirement ratio (RRR), effectively putting the money under lock and key at the PBOC (see chart below, courtesy of Reuters).

But the increased RRR didn’t catch all of the newly printed money. Extra RMB flowed into the economy and caused bouts of general price inflation, and even larger price increases in specific assets. Why did the prices of some assets increase relative to others? Inflation often doesn’t impact all prices equally, and when inflation causes the price of an asset to increase far above the increase in general prices, this is called abubble.

China’s propensity for bubbles is exacerbated by Beijing’s cap on the rate savers receive from bank deposits. The cap amounts to an indirect subsidy to some of China’s biggest firms, the state-owned-enterprises (SOEs). China’s state-run banks almost exclusively lend to SOEs, and because the banks pay so little interest to their depositors, the cost of capital to the SOEs that borrow from the banks is kept artificially low. So it does not pay Chinese savers to keep their money on deposit in the country’s state-run banks.

When the rate of general price inflation outpaced the interest rate available on bank deposits, Chinese consumers poured their savings into assets that were already overvalued, pushing up prices to irrational levels. In the wording of The Economist, “the hunt for good returns [caused by the cap on deposits] has over the past decade sparked investment frenzies in property, stamps, mung beans, garlic and tea, [and now stocks].” Of these frenzies, property investment is the biggest.

The growth in China’s money supply, compared with the money policy of America’s Fed

The second result of the currency peg was a massive accumulation of foreign asset holdings by the PBOC, which are referred to as China’s forex reserves. After the PBOC bought dollars from exporters, it used the dollars to buy dollar assets, mainly U.S. Treasury bonds. China has $3.56 trillion in forex reserves as of August 2015, the largest hoard in the world. $1.27 trillion of these are U.S. Treasurys. This is why people sometimes say China “owns” some of America’s debt.

China’s 2008 Stimulus

China’s export-led growth lasted throughout the 2000s. The more China exported, and the more upward pressure on the RMB this created, the more the PBOC’s peg flooded China’s economy with cash. To curb the RMB printing, and to ostensibly transform China into a consumer-led economy, China allowed a managed appreciation of the RMB versus the dollar, starting in 2005.

The RMB’s rise (note that downward trend reflects a stronger RMB versus the USD)

But this cocktail for growth soured in 2008. As global demand for Chinese products dropped during the Great Recession, China’s export-led growth model was in jeopardy. In response, China engineered a massive stimulus, monetary and fiscal.

Four trillion RMB ($586 billion) of new spending was allocated, largely to boost infrastructure; already indebted local governments were given broad access to the bond markets; state-controlled banks implemented a debt binge, with loans funneled to politically-favored SOEs, property firms, and local government infrastructure projects—which ballooned the size of Chinese banks past their American and Japanese peers; and, most importantly, China made all this new debt cheaper, which incentivized taking on even more debt, by easing monetary policy and slowing the RMB’s appreciation against the dollar.

As a result, debt surged. The Mckinsey Global Institute estimates the debt-to-GDP ratio in China rose from 158 percent in 2007 to 282 percent in 2014. In nominal terms, debt increased by over $20 trillion during this period, from $7 trillion to $28 trillion. This amounts to a quadrupling of Chinese debt in seven years, and a growth rate for debt that was twice the growth rate of nominal GDP (see chart, China’s debt growth, estimated by Goldman Sachs; LGFV stands for “local government financing vehicle”).

Much of this debt financed infrastructure and property development, as local governments felt pressure to meet arbitrary growth targets, and Chinese consumers continually parked their savings in real estate. Most is private-sector debt, or quasi-private debt issued by SOEs. As such, China’s corporate debt as a share of GDP is now over 160 percent, the highest in the world. Sitting at over $16 trillion, it is projected to reach $28 trillion by 2019, where it will make up 40 percent of corporate debt worldwide.

Of this huge debt load, half of all nonfinancial debt is property related. Analysts fromCredit Agricole, a French bank, put it this way: “[After the stimulus] private debt began to pick up … to finance large-scale real estate projects and new production capacity in industries such as steel, cement and mining, in many cases with links to the construction sector (real estate and infrastructure).”

China’s Property Bubble

PBOC’s RMB-inflation caused cheap lending that bid up the price of houses, and property developers saw no end to demand in sight. It is common for a moderately wealthy Chinese family to hold more than several uninhabited flats as investments. A sizeable property bubble resulted.

Beijing tried to cool the bubble several years ago, cracking down on lending by state-run banks. But that crackdown caused lending—still spurred by the PBOC’s easy-money—to move to the “shadow banking” sector, consisting largely of trust companies not subject to stringent bank regulation. When China tried normalizing monetary policy and easing back on local-government borrowing and spending, property prices began to fall. Slower construction exposed huge overcapacity in heavy industry and mining, which were feeding the property and infrastructure binge.

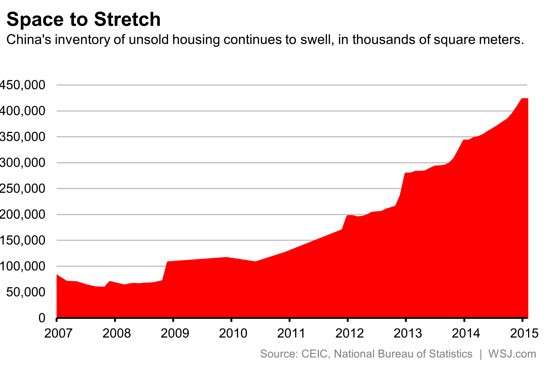

The oversupply in Chinese housing, courtesy of The Wall Street Journal

Because property contributes to a quarter of economic output (at the height of America’s housing bubble, property’s contribution to U.S. GDP was at most 5 percent), and because its “value underpins the banking system,” a slowing property sector began substantially weighing on China’s economy in 2014. Indebted local governments saw revenues dry up, to which new property development made a two-thirds contribution. To avoid a crash, China reversed all plans to deflate the property bubble further, noticeably in late 2014. This brings us to today.

China’s 2015 Stock Bubble and Crash

American media outlets have heavily covered China’s stock market this year, and many pundits see its crash as just another PBOC-created bubble. Here’s Ruchir Sharma, head of emerging markets and global macro at Morgan Stanley Investment Management: “When China’s economy slowed following the 2008 global financial crisis, Beijing pumped massive amounts of liquidity into the system. First that money went into the property market, later into the various debt-related products sold through the shadow banking system. But when property slumped and the shadow banks started to pose systemic risks, China had only one major market left to flood—stocks.”

‘When property slumped and the shadow banks started to pose systemic risks, China had only one major market left to flood—stocks.’

Sharma is mostly correct, but property is far more important in China than stocks. Chinese consumers had relatively little invested in the stock market, and the property bubble hasn’t gone away. Property consumes the vast majority of Chinese consumers’ savings. It is overwhelmingly their preferred investment vehicle. This stands in contrast to the United States, where household savings are usually divided among cash (including bank deposits), real estate, and stocks or bonds (often via holdings in pension plans).

As such, the Chinese government’s cheerleading of 2015’s ill-fated stock rally, resulting in a 40 percent crash since share prices peaked in mid-June, was largely a diversification strategy for its citizens’ savings. If Beijing could stoke and maintain a stock frenzy, maybe it would take pressure off of the slowing property sector.

In years past, Chinese savers avoided the stock market, seeing it for the casino that it is. The distrust of the stock market, and the love affair with real estate, has only been reaffirmed. The property market is now the only conduit for the savings of China’s politically important upper- and middle-class. In this light, the ridiculous efforts on the part of Beijing to prop up the stock market, spending some $1 trillion, or a staggering10 percent of GDP, become oddly rational. Beijing’s plunge protection attempts were a test run of the anticipated all-out war against the real-estate market.

Beijing’s Exit Strategy

Blowing more air in the housing bubble is now priority number one for the Communist Party. Halfway through 2015, the PBOC has reopened the monetary spigot: First, the Party reversed a plan to make it harder for local governments to borrow, and has ordered the PBOC to take on local government debt, which enables even greater local government borrowing. Next, the PBOC is again attempting to flood the system with liquidity, in the form of repeated reductions in both the benchmark interest rate and the RRR.

Blowing more air in the housing bubble is now priority number one for the Communist Party.

The new liquidity is being specially diverted to the property sector. Already, the government has drasticallyeased mortgage lending standards, and is giving unlisted property developers the special treatment of unrestricted access to the bond market.

Even more targeted liquidity funneling can be found in the domestic bond-issuance of property developer Evergrande. The firm recently sold debt at a lower cost than is available to many behemoth-SOEs. This suggests the PBOC could have subsidized the sale by buying some of the debt, or that the markets are simply pricing in state backing for the real-estate industry. Further stimulus measures directed at property should be expected going into the end of 2015.

China bulls look at these events and think Beijing can still manage the economy, and are sure the Party will continue on the path of economic liberalization. Others point out that property prices have rebounded in the last few months, especially in major cities, or note that consumer spending has yet to take a substantial hit.

Further stimulus measures directed at property should be expected going into the end of 2015.

Charles Hugh Smith, writing for The American Conservative, has an excellent article in response to bullish assessments on Chinese property. Smith outlines how current prices put real estate out of reach for most, prices are dropping outside of major cities, far too much developer inventory has been shoddily built and maintained. In his words, “[the] core question [is]—who’s going to buy the tens of millions of empty flats held as investments? What is the market value of flats nobody wants to buy or can afford to buy?”

Even if China is loosening monetary policy, as it is trying to do now, Beijing’s muscle to support the property bubble will eventually give out. Credit Agricole puts it this way: “[In the situation of] the declining efficiency of investment … more and more capital and debt have to be accumulated in an effort to maintain the level of growth and buy social harmony. These frantic efforts lead to excess, resulting in overcapacity (surplus production, run-up of inventories) and oversupplied property markets, especially in second- and third-tier cities. Rebalancing [is] now underway.”

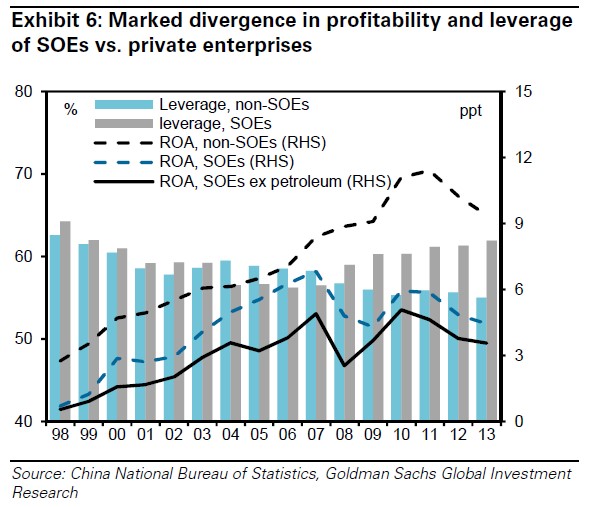

(SOE’s increasing leverage, decreasing ROA, courtesy of Goldman Sachs)

In other words, the debt load that fuels China’s real-estate machine is unsustainable. To avoid immediate collapse, debt-laden firms need to keep increasing leverage to push out product, which furthers excess capacity and pressures already-nonexistent profit margins.

How should China move forward? Ideally, China would allow the debt surrounding property to liquidate. This would restore robust growth, as future capital would be directed to projects better reflecting the preferences of Chinese consumers. Yet the weakness of the China model of governance will not allow this. Beijing will do everything to keep the bubble going, for fear that the sharp economic downturn required to liquidate the debt will foment civil unrest, or an inter-party war.

Under normal conditions, doing one’s best to sustain a bubble would cause the eventual correction to be more painful, or would ensure Japan-style stagnation. China, because of its currency peg, is not under normal conditions.

The PBOC’s Accidental Tightening

Just as it is possible for the government to make monetary policy too expansive, it is also possible for the government to make money policy too tight. China is more than in the midst of a boom-bust cycle caused by inflation—the PBOC is now flirting with a Great Depression, caused by a sudden, inadvertent tightening of monetary conditions.

The PBOC is now flirting with a Great Depression, caused by a sudden, inadvertent tightening of monetary conditions.

In the past, the RMB’s real value was higher than the value determined by its peg. This was due to a high demand for Chinese exports, foreign capital entering China, robust economic growth, and the assumption that the PBOC would slowly increase the RMB’s peg-value against the dollar. When the real value of the RMB was higher, maintaining the peg expanded the money supply, as it required creating extra RMB.

Now, because of the prospect of slower economic growth and the shaky valuations of RMB-denominated assets, the RMB in real terms is cheaper than the PBOC’s desired peg. If the peg went away, the RMB’s value would fall. This means that maintaining the peg accomplishes the opposite of what it did before—the peg is now sucking RMB out of China’s economy.

China has capital controls in place to stop money from being moved abroad, but in practice people can skirt these rules, especially the wealthy. As both foreign and domestic investors pull out, and as worried, wealthy Chinese try to diversify away from the RMB, the PBOC is being forced to defend the value of the RMB to maintain the currency peg by buying up RMB and selling dollars. In August alone, China sold off a record-setting $93.9 billion of forex reserves to buy RMB. Pulling RMB out of the economy causes liquidity to dry up, resulting in a sharp reduction in the growth rate of nominal spending, or nominal GDP. Producer prices are already down 5.4 percent from a year ago.

What about the PBOC’s current money stimulus? As the PBOC cuts rates and RRR, attempting to stoke more inflation and ease the debt load for the property sector, the RMB in real terms becomes even cheaper. This will only increase capital flight, forcing the PBOC to suck up more liquidity. The PBOC will try further monetary easing, which will again cause subsequent capital outflows—a downward spiral that economist Lars Christensen refers to as “monetary strangulation.”

How is monetary policy tightening when spreads are now lower in the bond market? Give it time. Interest rates can be a poor indicator of monetary conditions. Credit will tighten for firms dependent on bank borrowing before it tightens for firms in the bond market. And, of course, liquidity will be funneled towards property firms until the very end. Eventually, because of the PBOC’s peg, liquidity will tighten for real estate, too. That will precipitate the crash.

Here’s Wei Yao, an economist at Société Générale (SocGen), a French bank: “The battle to stabilise the currency has had a significant tightening effect on domestic liquidity conditions… The PBOC’s war chest is sizeable no doubt, but not unlimited. It is not a good idea to keep at this battle of currency stabilisation [sic] for too long.” J.P. Morgan analysts put things this way: “The liquidity injection via [the] RRR cut is mainly to offset the decline in interbank liquidity, which is related to recent capital outflows and FX intervention.”

Communism Locks China Into this Spiral

Why does China insist on continuing its currency peg? The direct answer is that maintaining capital controls requires maintaining the peg, if China is to have control over its monetary policy. Why does China insist on continuing capital controls? This again stems from the weakness of the Chinese system.

Abandoning capital controls would cause a sudden, massive flight of capital out of China.

China’s long-term interest lies in abandoning the capital controls outright. This would eventually stabilize the RMB, and make Chinese assets more valuable due to a liquidity premium (investors are more likely to enter if they are not prohibited from exit). In the near-term, however, abandoning capital controls would cause a sudden, massive flight of capital out of China. That would surely prick the property bubble, and the ensuing instability would threaten the Communist Party.

Again, SocGen’s Wei Yao: “Not letting the currency go requires significant FX intervention that will not prevent ongoing capital outflows but which will result in tightening domestic liquidity conditions; but letting the currency go risks more immense capital outflow pressures in the immediate short term, external debt defaults and possibly further domestic investment deceleration.”

Another factor in the continuation of capital controls and the currency peg must be the dollar-denominated debt of many Chinese firms. Pundits have pointed out that Chinese foreign-currency debt is nothing compared to the degree of dollar debt that precipitated the 1997 Asian Financial Crisis.

True, but many Chinese issuers of dollar bonds are firms in the all important real-estate sector. Nomura, a bank, estimates external liabilities amount to $1.135 trillion, $405 billion of which is bond issuance, the rest being international bank loans.Mingtiandi, a Chinese real-estate intelligence firm, estimates that over a third of developer debt is not in RMB. Jeffries and JP Morgan put total developer debt exposed to the dollar even higher, at 40 percent.

The devaluation was in small part a warning to property-sector issuers of dollar debt who have not hedged against RMB depreciation.

As such, the recent RMB devaluation should be thought of in two ways. It was not a sop to exporters, nor was it an attempt to allow market forces to more greatly sway the RMB. Rather, the devaluation was in small part a warning to property-sector issuers of dollar debt who have not hedged against RMB depreciation, and was in large part due to the PBOC’s peg pulling too much RMB out of the economy. There will be more devaluation.

But keeping the peg in place and allowing what looks to the market like knee-jerk devaluations only makes investors place more bets on a falling RMB, which further goads capital flight. Citigroup analysts write that, “After [the] recent FX regime shift, it’s also not realistic to assume the renminbi should stabilize after [a] mere 3 per cent depreciation.” SocGen projects a further 6.2 percent depreciation by the end of the year. In other words, unless the PBOC abandons the currency peg altogether, thus abandoning capital controls, it is backed into a corner.

Instead of the quick knock on the head that liberalizing capital controls would bring, along with allowing the RMB to float, China is opting for a slow and excruciating monetary strangulation. When the property bubble does burst, Chinese consumer spending will be radically reduced in a reverse wealth effect as savings are wiped out. In the words of hedge fund manager James Chanos, China is on a “treadmill to hell”because of the “heroin of property development.”

Supply-Side Disasters to Come

In the meantime, Beijing will double down on already shoddy supply-side policies. If a firm is to know how much to produce and invest, prices must reflect the needs and wants of Chinese consumers. Inflationary monetary policy has already distorted the price mechanism in China. Price signals are further hampered because of the Party’s unwillingness to allow any large default or closure of a state-owned bank or company.

If a firm is to know how much to produce and invest, prices must reflect the needs and wants of Chinese consumers.

Couple this with a systemic lack of transparency, and you get moral hazard on a gargantuan scale. “There is little credit differentiation in China,” says Becky Liu, a strategist at Standard Chartered in Hong Kong. Pedro de Noronha, managing partner at Noster Capital LLP, claims, “I don’t believe a single number in their balance sheets or cash flow statements.”

As many Chinese firms dip further in the red, the inherent weakness of the Chinese system will again kick in. Beijing will move to consolidate the failing firms under ever-larger state-run behemoths, opting for inefficiency over the necessary failure of capitalism. China will thus balk at the liberalizing reforms China bulls are hoping for, and expand state control of industry, which will lead to further crackdowns on foreign competitors operating within China.

In the end, the greatest loser will be the Chinese people, especially the poorest yet to experience economic development. Such is the nature of central planning.

Back to America

Does any of this threaten America? A Great Depression in China shouldn’t capsize America’s economy, although we certainly have our own problems. The most immediate threat China poses will be geopolitical. As strains on Xi Jinping’s leadership increase due to economic turmoil, factions already annoyed by Xi’s consolidation of power and crackdown on corruption could attempt a coup. These factions might be more nationalistic or Maoist than is current leadership, which should surely worry policymakers in America.

Xi will further solidify power at home, and seek to distract from the economic turmoil by flexing China’s military muscle abroad.

To guard against this, Xi will further solidify power at home, and seek to distract from the economic turmoil by flexing China’s military muscle abroad. The recent Chinese naval foray off the coast of Alaska is only the beginning, and the West should worry about the brewing conflict between China and Japan over the Senkaku islands. American leadership must to be prepared with a measured response, operate from a position of strength, and be committed to maintaining pax Americana in Asia.

A more distant harbinger is the admiration of China’s model from many Westernpoliticians, business leaders, and academics. This is oddly reminiscent of those who were apologists for the Soviet Union or Nazi Germany. For example, Robert Reich has praised China’s centralized economic planning, and Paul Krugman has praised China’s blowout stimulus. Jeff Immelt, General Electric’s CEO, says China’s government “works.”

But the American model based on limited central government, representative democracy, and human freedom is much better for economic growth. Not only does China’s model not “work,” it has perpetrated untold amounts of human suffering.

Not only does China’s model not ‘work,’ it has perpetrated untold amounts of human suffering.

On this preeminent issue, Pascal-Emmanuel Gobry (who has previously appeared in The Federalist), writing forThe Week, says it best. I wish every American would read his article. Here are the best parts:

“Authoritarian governments seem stronger than democratic governments, because they are constrained by fewer rules, but in reality they are weaker. Because their rule is based on force, not law or common consent, they must exist in constant fear of overthrow. Western pundits look at the Chinese Communist Party and see strong, far-sighted technocrats. But the men inside are actually terrified of anything that might cause unrest, and know very well that they are more like rodeo riders hanging on for dear life than sovereigns.…”

“What’s more, because authoritarian governments do not have the rule of law, and do not have accountability through a transparent, agreed-upon process, they are inevitably corrupt … Meanwhile, the U.S. has one of the most precious pieces of economic infrastructure ever designed by man: the rule of law. Building ambitious infrastructure projects is hard in the U.S., because the U.S. has a strong culture of property rights. This sort of infrastructure may be invisible, but it is the kind most conducive to long-term economic growth. People whose assets might be taken overnight by a neighbor or by the government don’t invest much. Just ask most people in sub-Saharan Africa.”